26 July 2021: Clinical Research

Saliva pH and Flow Rate in Patients with Periodontal Disease and Associated Cardiovascular Disease

Pompilia Camelia Lăzureanu1ABDEF, Florina Popescu2ADEF*, Anca Tudor3ACDE, Laura Stef4BD, Alina Gabriela Negru5D, Romeo Mihăilă6ADEFDOI: 10.12659/MSM.931362

Med Sci Monit 2021; 27:e931362

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Periodontal disease, a frequent oral health problem, is connected with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to assess the unstimulated saliva flow rate and saliva pH as markers of the severity of periodontal disease in patients with cardiovascular disease.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A cohort of 155 patients (78 men and 77 women, aged 30-92 years) was included, and a structured questionnaire obtained information about their health status, oral healthcare behaviors, and eating habits. An oral examination was performed to assess periodontal status and presence of dental calculus. The unstimulated whole salivary flow rate and salivary pH were measured. An oral hygienization was performed, and 3 months later, salivary flow rate and pH were reevaluated.

RESULTS: A severe form of periodontal disease was found in 22.4% of patients. Disease severity was strongly correlated with low pH values (6.25 in stage IV periodontal disease), lower salivary flow rate (0.28 mL/min), smoking, poor oral hygiene habits and obesity, with no significant differences by sex. We observed a significant increase of pH (up to 6.30±0.17) in patients with severe periodontal disease (P=0.001) and salivary flow rate values (0.29±0.07 mL/min; P=0.014) 3 months after oral hygienization. There was a strong association between the severity of periodontal disease and presence of cardiovascular disease (P=0.001).

CONCLUSIONS: Our study suggests that the decrease of salivary flow rate and pH level might be associated with the severity of periodontal disease.

Keywords: Cardiovascular Diseases, Fluxum, periodontal diseases, Saliva, Aged, 80 and over, Follow-Up Studies, Health Status, Hydrogen-Ion Concentration, Obesity, Oral Hygiene, Smoking

Background

Periodontal disease, a complex inflammatory disease initiated by bacteria of the oral biofilm [1], is one of the most frequent oral health problems and is possibly involved in the evolution of other chronic systemic diseases [2] by contributing to systemic inflammation [3]. The worldwide prevalence of periodontal disease is reported to be between 20% to 50% [4], with 5% to 11% of adults in Europe reported to have a severe form of periodontitis [5]. Studies performed in several areas in Romania have also shown that periodontal disease is a frequent health problem in 41% to 65% of the adult population [6–8], suggesting the need for further efforts in implementing oral healthcare programs to better control this pathology. The severity of periodontal disease can impact the general health of a population, as multiple studies have reported an association between periodontal inflammation and the increased risk of cardiovascular disease [9,10].

Although the exact mechanisms linking periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease are yet undiscovered, research has shown that periodontal disease is associated with cardiovascular mortality [11]. According to several studies, oral bacterial can enter the systemic circulation [12], especially in patients with gingival inflammation and multiple dental interventions [13]. At the same time, the presence of bacteremia has been shown to influence the appearance and progression of atheromatosis in animals [14] and humans [15], with studies showing invasion of the endothelium in vitro [16].

Recent studies on oral biofilm in patients with periodontal disease found that bacteria (

The persistent inflammation caused by bacterial infection is an independent predictor of acute cardiovascular events [21]. In addition, improved oral hygiene has been shown to reduce cardiovascular events in patients [22]. Salivary secretion has an important role in maintaining the health of the oral cavity [23] by adjusting the pH level and thereby intervening in the regulation of teeth mineralization amd gum health [24]. The saliva flow rate and saliva composition depend on various factors such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI) [25], medication use [26], and oral hygiene. Any modification in saliva properties can lead to oral health problems, including caries, dental calculus, gingivitis, and periodontal disease [27].

Gingival crevicular fluid is not easy to collect in a typical dental practice [28], but rather requires a skilled health provider using a correct technique [29]. Saliva is available in a large quantity, is easy to collect, is suitable for repetitive examinations, has been proven to be a suitable noninvasive diagnostic tool, and is suitable for mass-screening programs [30]. In addition, biomarkers have been identified in saliva that originate from both biofilm bacteria and the host.

Studies have shown that exposing the gingiva to saliva with a neutral or more alkaline pH level improves gingival healing in patients with periodontitis, while a lower pH level might have a superficial necrotizing effect [31]. Furthermore, bacteria multiplication, such as by

Changes in saliva properties influence the progression of periodontal disease, which could increase cardiovascular risk. The purpose of this study was to investigate the correlation between saliva pH and flow rate and the severity of periodontal disease in patients with cardiovascular disease and to determine if saliva pH and flow rate variation could be used as potential markers of disease severity. Our objectives were to (1) evaluate the periodontal status and oral healthcare habits of patients with periodontal and cardiovascular disease; (2) identify factors that could influence the saliva pH and saliva flow rate in the selected group of patients; and (3) assess the modification of salivary pH and salivary flow rate after dental hygienization.

Material and Methods

STUDY PARTICIPANTS:

The inclusion criteria for the study group were as follows: patients with cardiovascular disease, including arterial hypertension, valvular disease, myocardial infarction, stable coronary disease, chronic heart failure, and peripheral artery disease. A control group consisted of patients without cardiovascular disease. Patients in both groups agreed to undergo an oral health examination and oral healthcare services.

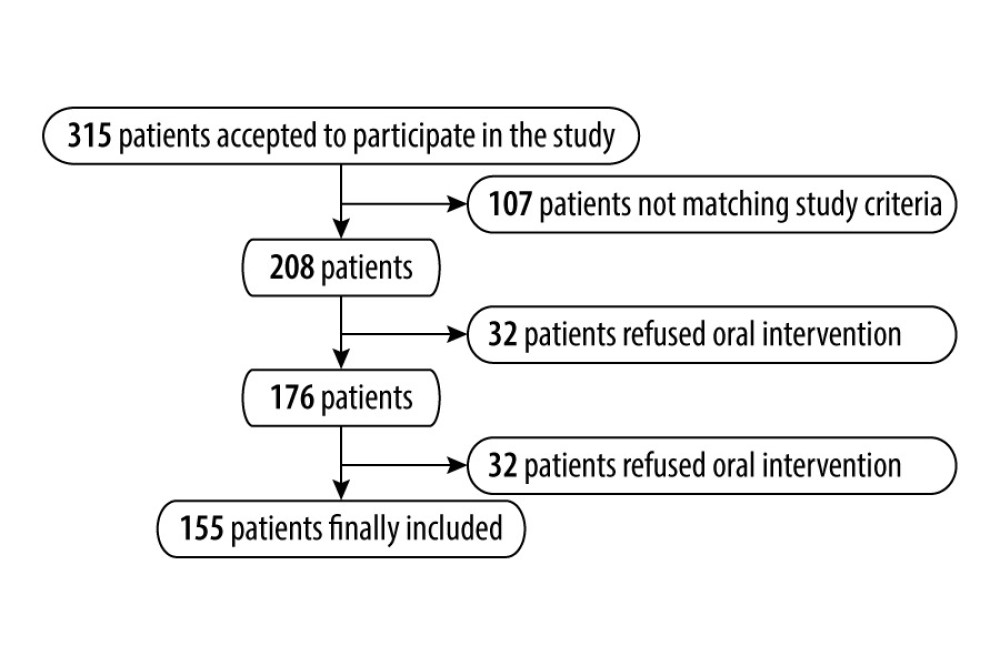

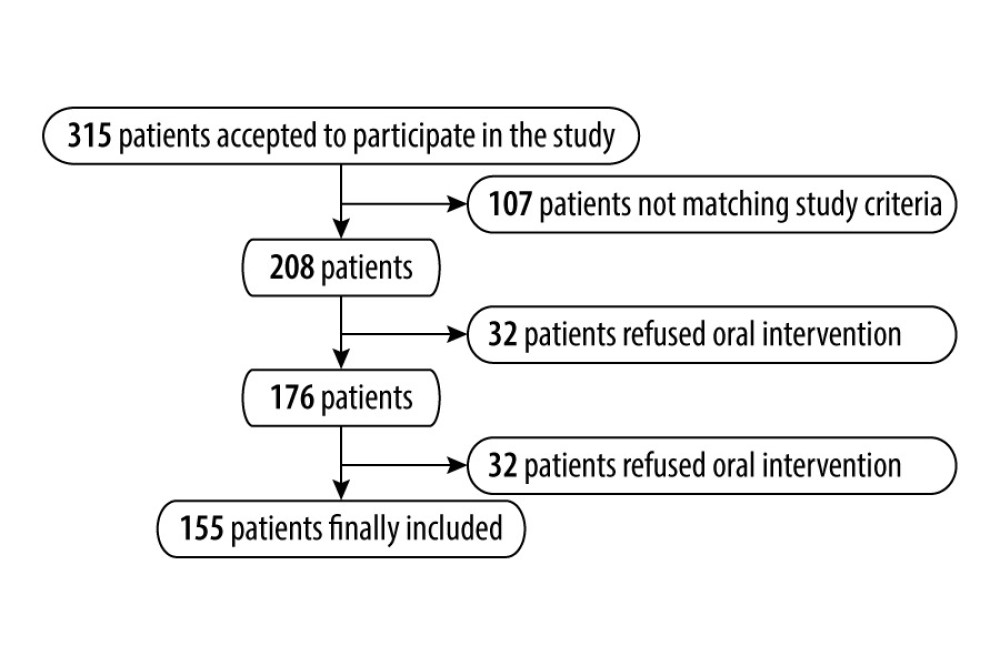

The exclusion criteria were as follows: hemodinamically unstable patients, situations that could influence systemic inflammatory response (such as recent surgical interventions, including dental surgery in the last 6 months), signs of acute infections or patient under treatment for acute/chronic infections, use of anti-inflammatory medications, other chronic diseases (such as diabetes, kidney disease, pulmonary diseases, bronchial asthma, autoimmune, and autoinflammatory diseases under treatment), malignancy, cognitive and psychiatric disorders, lactation or pregnancy, oral lesions other than dental calculus, caries, and generalized periodontal disease. The final patient sample selection is shown in Figure 1.

Patients’ medical information was obtained from their medical records. A physical examination assessed anthropometric measures including weight, height, and BMI. An initial group of 315 patients agreed to participate to the study. Of those, 107 patients were excluded for not meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria. From the 208 remaining patients, 32 refused oral intervention. Of the remaining 176 patients, 21 did not come to the 3-month follow-up and were also excluded. Of the total of 155 patients finally included in the study, 112 had cardiovascular disease and 33 were in good general health (Figure 1).

Subsequently, the 155 patients completed a structured questionnaire that collected information on their oral hygiene habits (frequency of teeth brushing per day, use of mouth rinse, dental floss, frequency of visits to the dentist, dental calculus removal procedures), alimentation habits, and physical exercise.

ORAL HEALTH EXAMINATION AND DENTAL SCALING:

Oral examinations of all patients were conducted by the same experienced dentist to minimize evaluation bias. Periodontal status was evaluated according to the 2018 periodontal disease assessment recommendations [36]. Periodontal disease severity was assessed using a plane examination mirror (Carl Martin, Germany) and dental probe (1-mm periodontal probe, Fima Instruments). The dentist recorded incidences of bleeding on probing, the pocket depth of all teeth, and clinical attachment loss using 6 index teeth (all first molars, or second molars as substitutes, the upper right central incisor, and lower left central incisor). Third molars, root remnants, and dental implants were excluded from all measurements. Clinical attachment loss was determined with the periodontal probe, and measurements were recorded on 4 sites per tooth, from the cemento-enamel junction to the base of the gingival sulcus. Pocket depth was measured from the gingival margin to the base of the gingival sulcus. Bleeding on probing was noted when it was present during or immediately after introduction of the probe in the gingival sulcus and on performing a smooth lateral move along the pocket wall on 5 sites per tooth (buccal and oral). No radiological assessments were performed owing to technical difficulties.

The oral health index-simplified (OHI-S) index [37] was calculated using 6 index teeth (1.1, 1.6, 2.6, 3.1, 3.6, 4.6). In cases of missing teeth, the adjacent teeth were used, and in cases of missing adjacent teeth, the opposite teeth were used. If dental plaque was found during the examination, the dentist proposed and performed oral hygienization for patients who agreed with the procedure. Dental scaling is defined as supra-gingival scaling to remove the plaque and calculus for preventive oral health. A Woodpecker DTE D1 ultrasonic scaler with Satelec probes (GD1, GD2) was used for supra-gingival scaling of all dental surfaces.

Three months later, the OHI-S score, clinical attachment loss, salivary flow rate, and saliva pH level were reevaluated using the same examination methods.

SALIVA ANALYSIS:

Saliva analysis, performed for all participants in the study, consisted of determining the unstimulated whole salivary flow rate and measuring the salivary pH level before any dental procedures were conducted. The whole saliva collection procedure was explained to the patients to ensure compliance. Unstimulated whole saliva was collected following the drainage technique [38]. Patients were instructed to let saliva drop from their mouths into a graded tube. This was carried out between 8: 00 AM and 10: 00 AM on the day of the oral examination before dental procedures were preformed. For this morning saliva collection, patients were asked to not smoke, eat, or drink any beverages except water, and to not perform any particular oral hygiene except rinsing the mouth with drinking water to avoid influencing the final results.

The patients were given drinking water and asked to rinse their mouth out well. Five minutes after this oral rinse, patients were comfortably seated and asked to spit whole saliva into a sterile grade collection tube for 10 min. They were asked to refrain from talking and to drop the head down and let the saliva run naturally to the front of the mouth. The patients were also asked to not cough up mucus during saliva collection. All saliva collections were supervised. After recording the saliva flow rate results, the pH of the saliva was measured immediately to prevent any deterioration of the sample.

Salivary pH level was measured using a single-electrode digital pH meter (Mettler Toledo Seven Compaq PH, AutoInc, USA). The electrode was submerged in hydrochloric acid of 0.1 N standard solution the night before measurements. The pH meter was then calibrated using freshly prepared buffers of pH 7 and pH 4. Following this, the electrode was kept dipped in double-distilled water. Prior to dipping the electrode in the sample, it was gently and completely dried each time using fresh sterile tampons. After analyzing the pH, the electrode tip was again washed with a gentle stream of distilled water and then dipped in the double-distilled water.

The dentist performed dental scaling to remove the plaque and calculus and used an airflow and ultrasound scaling technique, which was followed by professional brushing. Subgingival scaling and root planing were not performed. Patients agreeing to oral hygienization were reexamined 3 months after the procedure. The dentist reevaluated the clinical attachment loss and determined the OHI-S score, salivary flow rate, and salivary pH level. The results were compared with the initial measurements.

DEFINITION OF OTHER VARIABLES:

Patients were asked about their living conditions (rural/urban area), education level, which was categorized as no education, elementary (≤8 years), or higher education (high school and university), and level of physical activity in the last 12 months (sedentary, 1–3 h activity per week, >3 h per week).

Smoking, coffee, and alcohol consumption was recorded. Patients were classified as smokers if they reported cigarette use for at least 5 years, and alcohol consumption was regarded as at least 3 occasions of drinking alcohol per week. No heavy alcohol drinkers were reported. Oral healthcare habits were measured as follows: frequency of tooth brushing, use of dental floss, use of mouthwash, and number of visits to the dentist per year.

DATA ANALYSIS:

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17. For numeric variables, descriptive statistics were performed, and the comparisons between these variables were made with the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for more than 2 independent series and with the Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons between 2 sets of independent values with no Gaussian distribution. For comparisons between 2 paired numerical series, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The correlations between numerical variables were made by determining the Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Results were considered significant with a value of

Results

ORAL HEALTHCARE OUTCOMES:

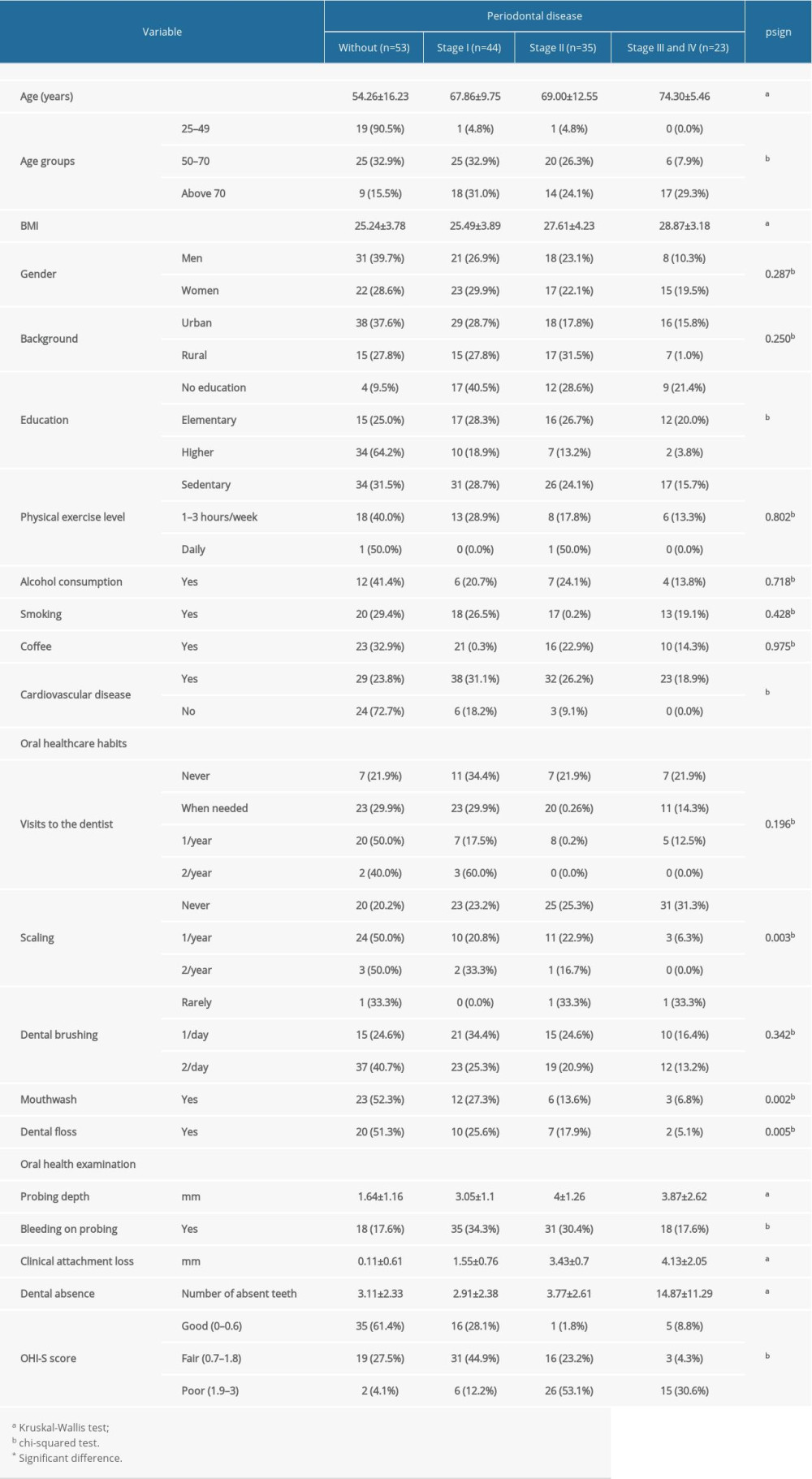

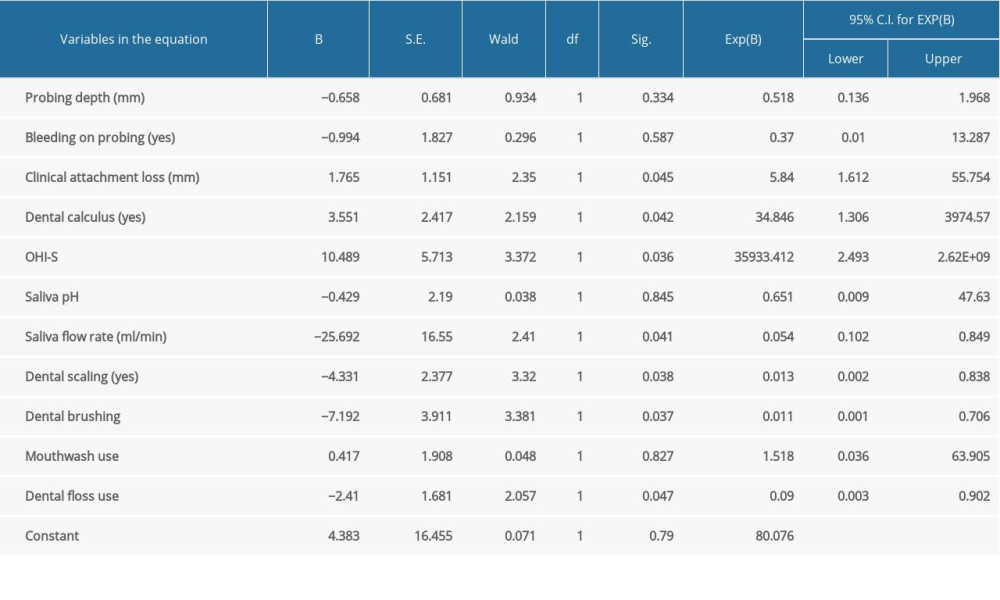

Concerning oral healthcare, 20% of all patients reported that they had never been to a dentist, and 77.5% of patients with periodontal disease had never had dental scaling. Furthermore, 24.5% of patients with periodontal disease were not previously diagnosed by an oral healthcare provider and did not benefit from any specific treatment. The use of mouthwash and dental floss was not a common practice among the patients in the study group, and this was associated with the severity of periodontal disease (

SALIVA PH:

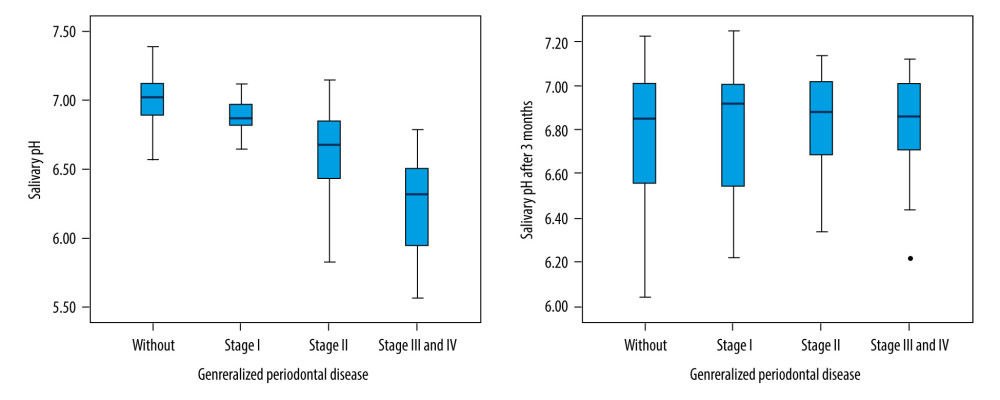

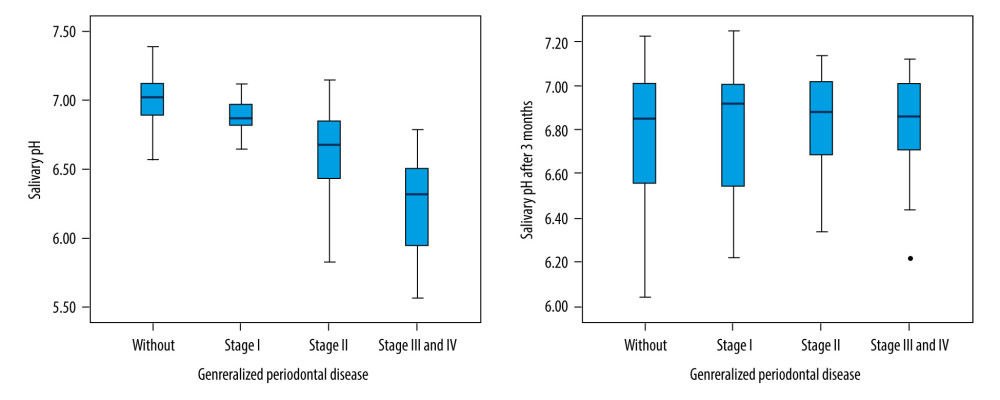

In all patients, the saliva pH level decreased with the increase of the severity of periodontal disease (Kruskal-Wallis test,

We did not find an association between salivary pH level and age, sex, oral hygiene practices, eating habits, exercise habits, and alcohol consumption (

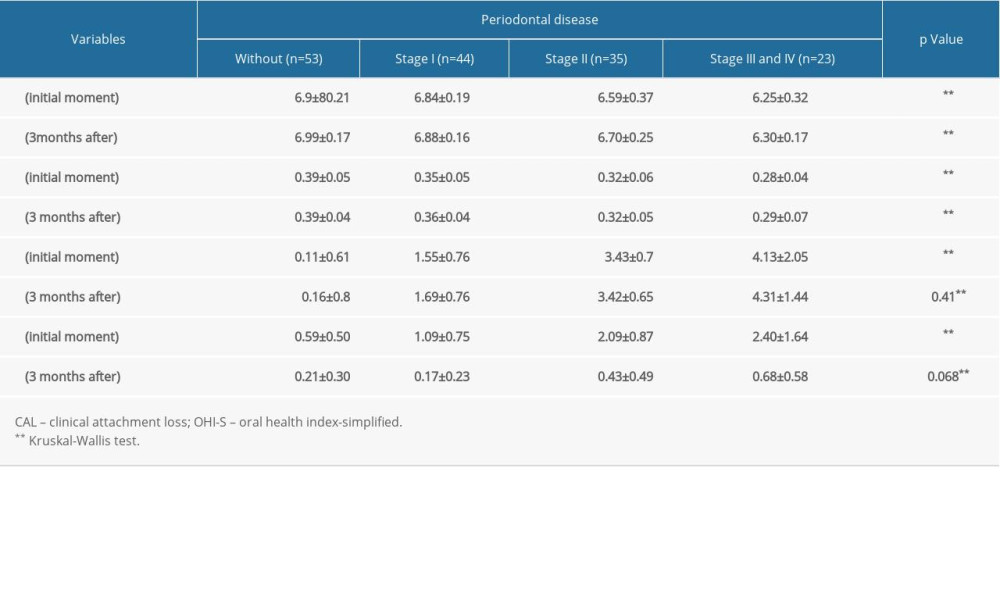

Correct oral hygienization induced changes in salivary pH levels, which became significantly more alkaline at 3 months after dental scaling (Kruskal-Wallis test, P=0.001) (Figure 2).

SALIVA FLOW RATE:

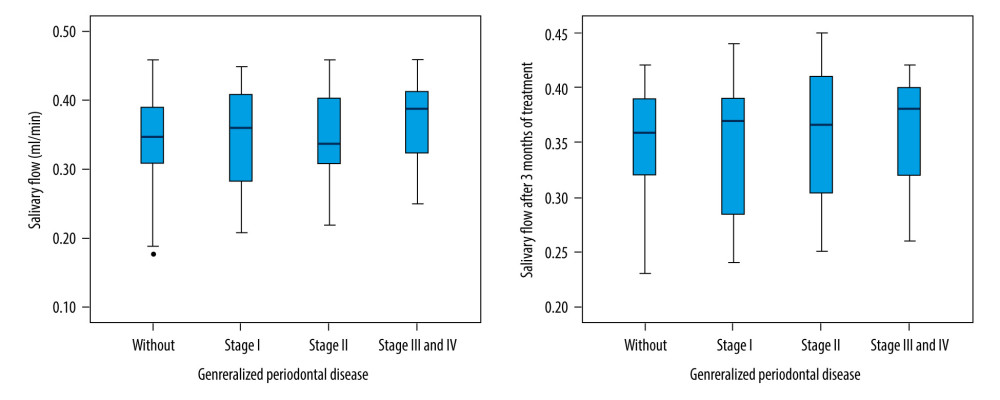

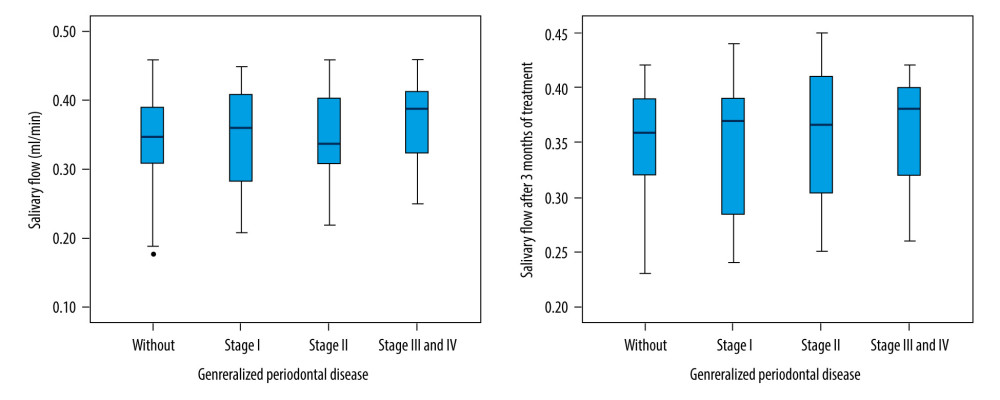

Patients with severe periodontal disease had a decreased salivary flow rate (Kruskal-Wallis test,

Furthermore, the oral hygienization procedure significantly improved the salivary flow rate after 3 months in patients with stage II, III, and IV periodontal disease (Kruskal-Wallis test, P=0.001) (Figure 3).

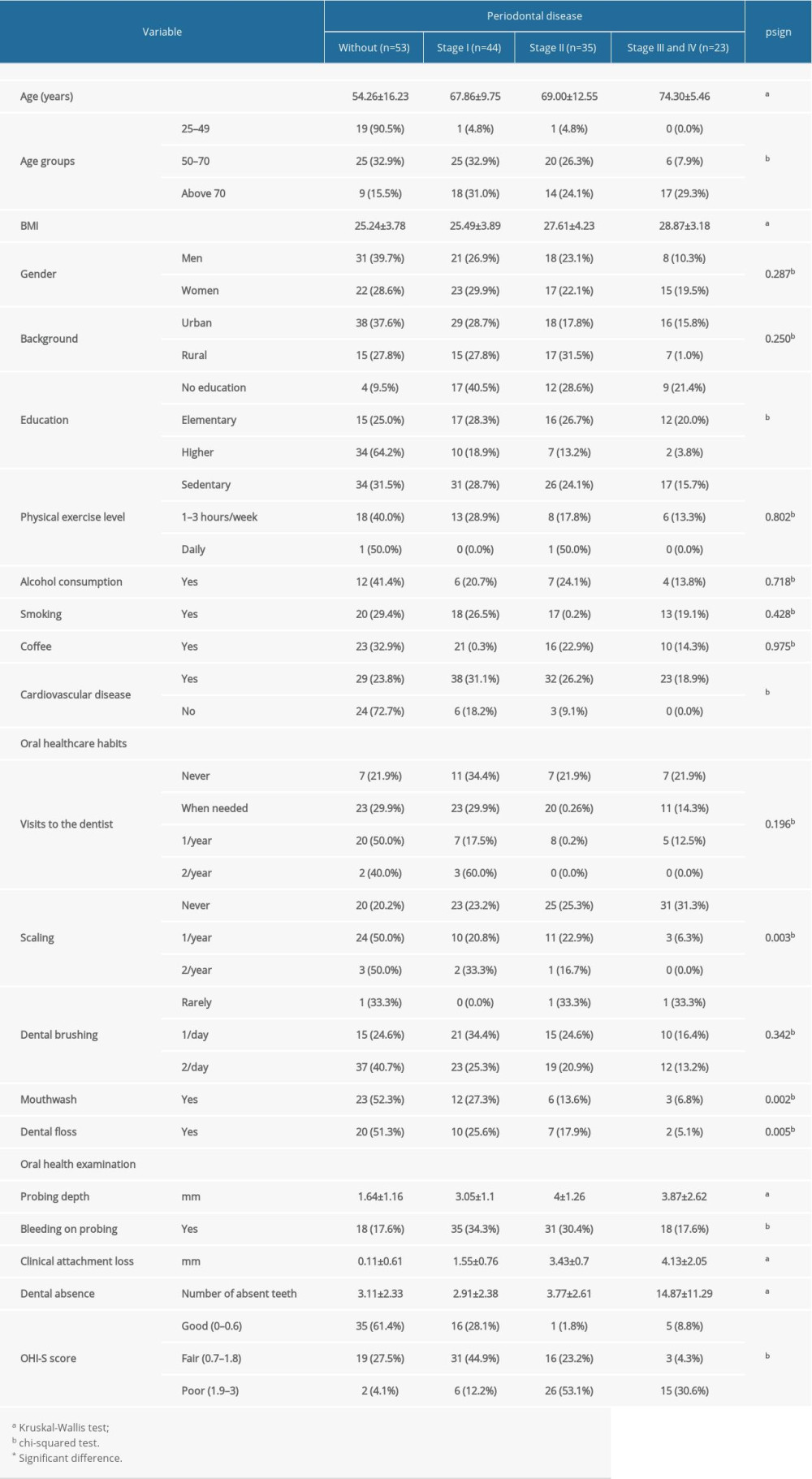

Patients with severe periodontal disease had a higher OHI-S score at baseline (Kruskal-Wallis test, P<0.001), and, at 3 months after treatment, the differences between OHI-S scores after periodontal treatment were insignificant (Kruskal-Wallis test, P=0.068). Furthermore, patients with severe periodontal disease also had increased clinical attachment loss at baseline and at 3 months after treatment (Kruskal-Wallis test, P<0.001), and there were no significant improvements at 3 months after superficial scaling (Table 2).

Three months after dental scaling, the salivary pH level increase was not significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test,

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE:

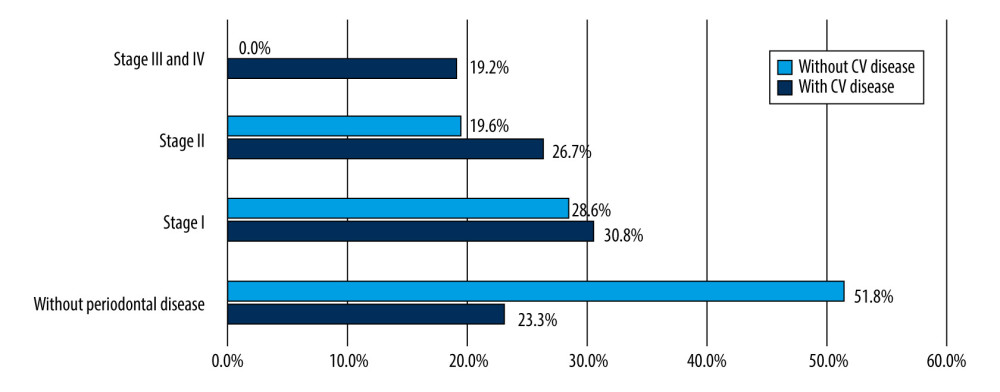

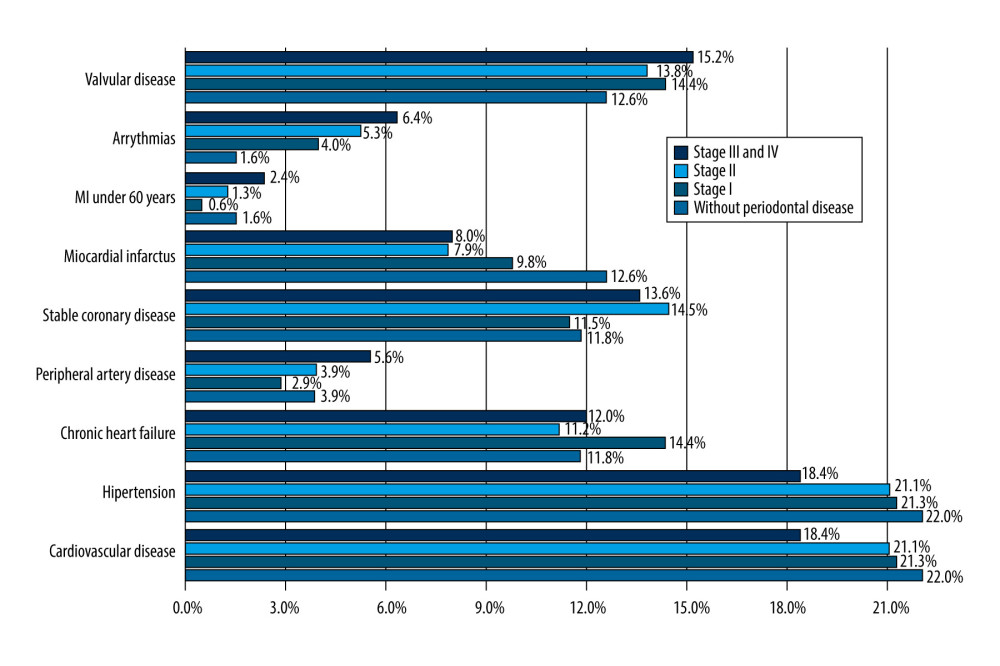

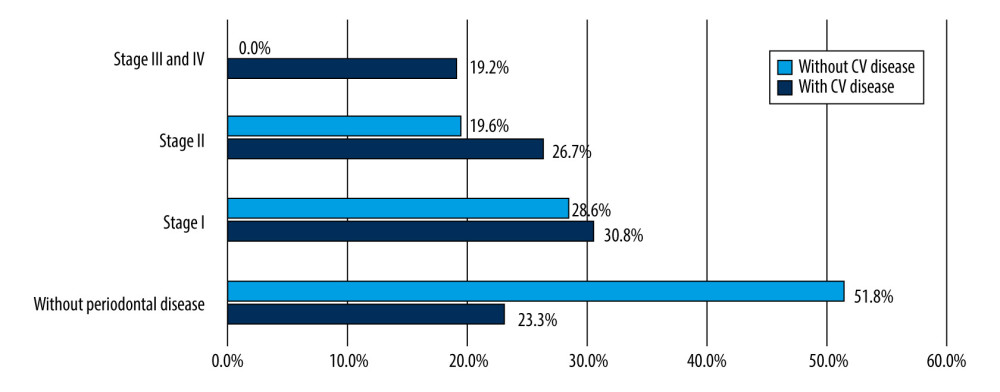

There was a strong association between the severity of periodontal disease in patients with cardiovascular disease compared with patients without identified cardiovascular disease (P=0.001). All patients with severe forms of periodontal disease enrolled in the study had associated cardiovascular disease (Figure 4).

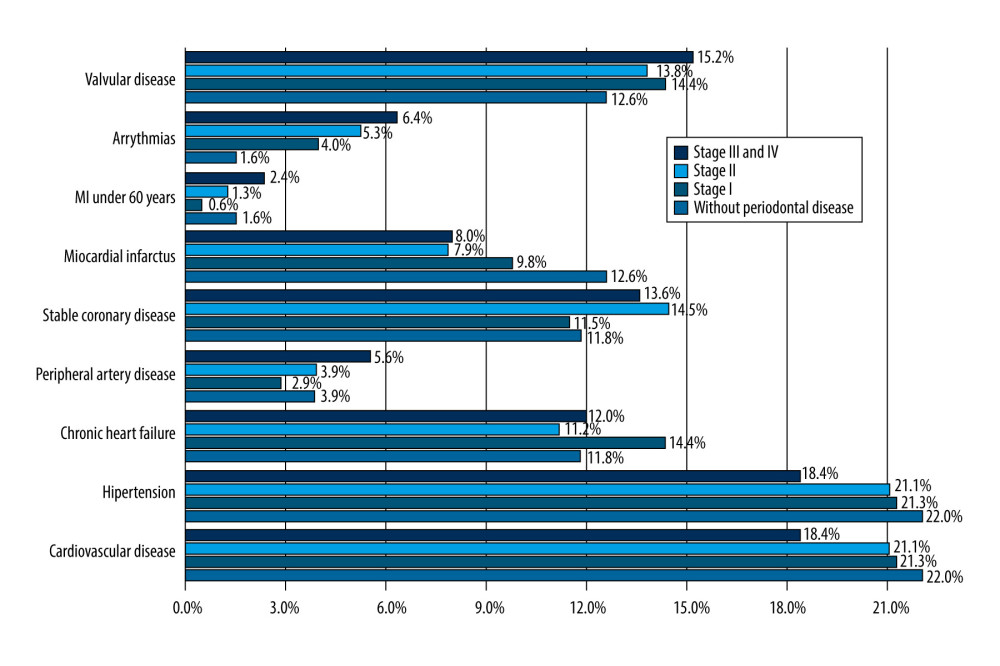

In total, 78.7% (122) of patients included in the study had cardiovascular disease. All had hypertension under treatment, and some patients had other associated cardiovascular diseases: 61.67% had stable coronary disease and 45.8% had myocardial infarction. In addition, 60.75% had degenerative valvular disease and 20.8% had arrhythmia. All patients with periodontal disease had a significantly higher prevalence of arrhythmia (P=0.01), peripheral artery disease, and coronary disease (P=0.032). The association between valvular disease and the presence of periodontal disease (regardless of the severity) was nonsignificant (P=0.23). Arrhythmia and myocardial infarction at a younger age (<60 years) was more frequent in patients with a severe form of periodontal disease (6.4% and 2.4%, respectively) (Figure 5).

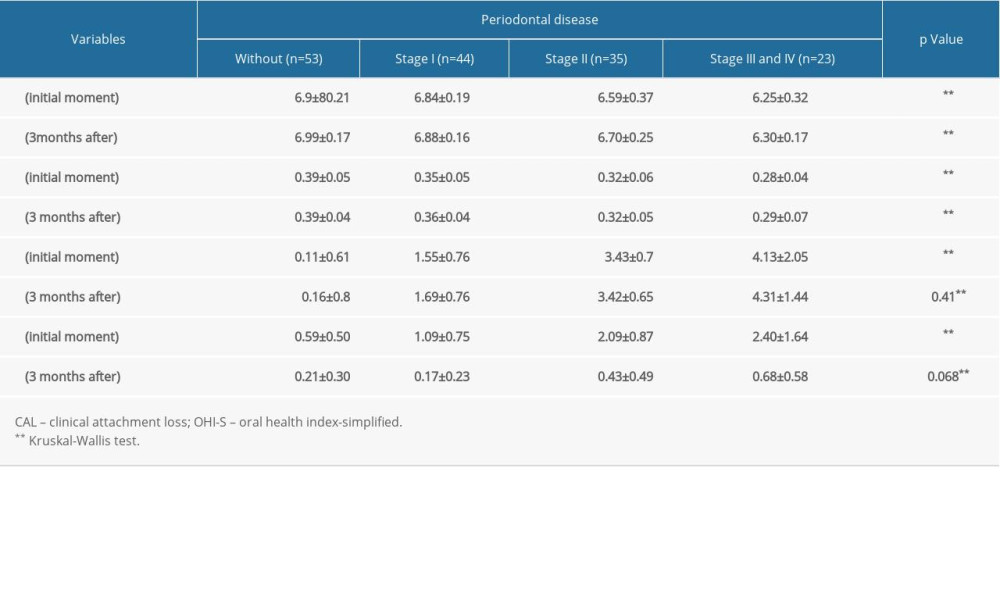

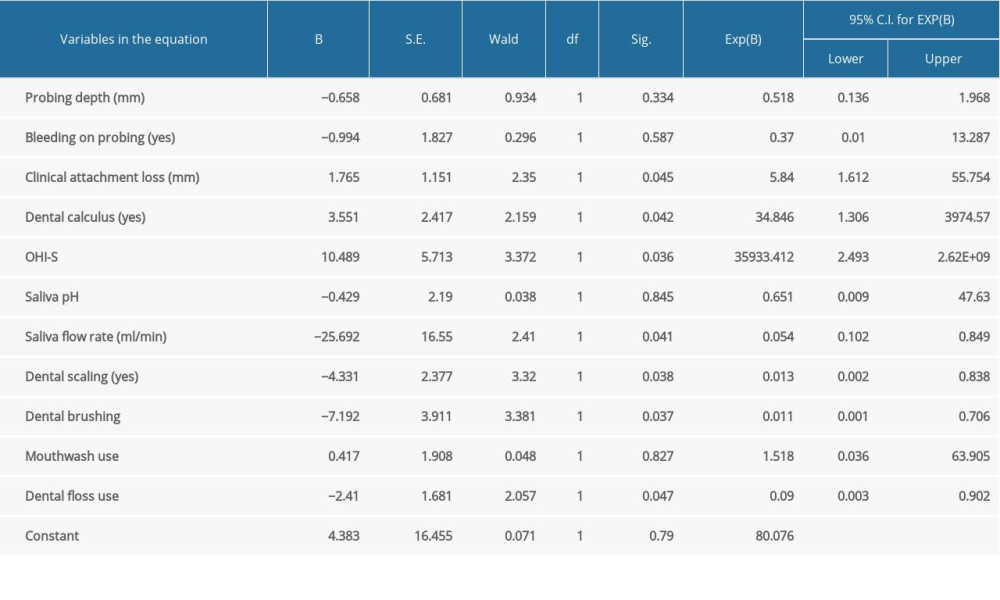

By conducting logistic regression analysis with cardiovascular disease as a dependent variable, we observed that poor dental hygiene (as evaluated with the OHI-S score) was a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Adapting oral health measures such as regular teeth brushing, flossing, and oral hygienization might have a protective role. Moreover, clinical attachment loss was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and an increased saliva flow rate had a protective role (Table 3).

Discussion

ORAL HYGIENE:

Overall, our patients had an alarmingly low oral health hygiene score, with 63.87% of them never having had dental scaling. Other studies have acknowledged the necessity of the participation of a dental hygienist in a periodontal care program [50]. Only 18.2% of our patients with periodontal disease and associated cardiovascular disease reported having regular visits to their oral healthcare provider (once or twice per year) and 6.45% reported having regular scaling, but none of these patients reported receiving specific periodontal treatment prior to our evaluation. A Korean study with a large number of patients [45] showed that constant oral hygiene decreases cardiovascular risk by 14%, and these patients might also have fewer acute cardiovascular events.

Moreover, lack of a proper oral hygiene routine leads to tooth loss, with a median of 5 missing teeth in patients with an OHI-S score >1.9 in the present study. Missing teeth have been associated with high cardiovascular risk, although the mechanism is still unknown [45,51].

Education level also seems to have a strong impact on the progression of periodontal disease, as we observed that patients with a higher education level were more adherent to oral healthcare and had less severe forms of periodontal disease. Access to information and a proper oral health education has a beneficial impact, according to Boillot et al [52].

SALIVA PROPERTIES MODIFICATION IN THE PERIODONTAL GROUP:

In the oral cavity, saliva helps maintain the pH level near neutral (6.78±0.04) [53], but studies have shown that patients with periodontal disease tend to have a more acidic pH [54], which is similar to our findings. The average pH level in our control group of healthy periodontal individuals was 6.982±0.207. Average pH decreased with the increase of the severity of periodontal disease and was highly associated with smoking habits in our study group. Furthermore, the salivary pH level of our patients was not associated with sex, similar to other findings [55], place of residence, and oral hygiene habits, although some studies [56] have shown evidence of differences between men and women. A high proportion of our female patients were smokers (41.5%), with an average of 15.5 packages per year, compared with an average of 15.1 packages per year in men, a factor that could explain the absence of a significant difference in salivary pH between men and women in our study group [57].

SALIVA FLOW RATE IN THE PERIODONTAL GROUP:

A Japanese study with a large number of participants showed that patients with lower salivary flow rates had an increased risk of developing periodontal disease [58]. In our study, we observed that the unstimulated salivary flow rate decreased with the increase of the severity of periodontal disease, with no significant difference between the moderate and severe stage of the disease; however, the unstimulated salivary flow rate remained lower than in the control group. Other studies also found no significant difference in salivary flow rate in different stages of periodontal disease [59]. We found no significant difference between men and women (P=0.058, Mann-Whitney U test), which was similar to the findings of other studies [60,61]. However, the same high proportion of women in our study were smokers, and smoking is proven to decrease the salivary flow rate [62].

In the present study, the salivary flow rate and salivary pH level showed a significant improvement 3 months after oral hygienization in patients with severe forms of periodontal disease, although they remained lower than in patients with no periodontal disease. Therefore, these factors are potential tools for periodontal disease follow-up.

Furthermore, the severity of periodontal disease and acute cardiovascular events (such as myocardial infarction at an early age) seem to be influenced by severe forms of periodontal disease [63]. In the present study, our group of patients with a severe form of periodontal disease also had more frequent arrhythmias and myocardial infarctions at an early age. Lower pH levels and lower saliva flow rates were reported in patients with cardiovascular disease [64] and are potential aggravating factors of existing periodontal disease and can therefore lead to the progression of systemic inflammation and further influence systemic diseases [65]. Of course, we have to keep in mind that older patients have multiple associated diseases and multiple treatments that could also influence the saliva pH level and saliva flow rate [66], which could further aggravate oral health status.

Our results showed that associated oral health problems such as dental plaque may be additional risk factors for the development and progression of periodontal disease, whereas obesity and smoking are associated with more severe forms of periodontal disease. Further, obesity and smoking are implicated in cardiovascular disease occurrence [67,68]. These are all modifiable risk factors for periodontal disease [3].

The studies published until now revealed that there is an independent and a significant association between severe periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease [69]. In this context, although a very complex pathology by itself, periodontal disease can be considered a potentially modifiable nontraditional risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which can be considered in cardiovascular pathology [42].

Programs promoting oral health are very important [70] for prevention of diseases related to oral health, and there could be a significant benefit in implementing an educational program addressed to hospitalized patients. Studies show that even Romanian adolescents have lower oral health-related knowledge than other adolescents in Europe [71], and there is an opportunity for improvement through adequate oral health programs [72].

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY:

The final sample of patients included in the study was small, with an uneven distribution regarding the presence or absence of cardiovascular disease. Patients were reevaluated 3 months after dental scaling, but long-term surveillance is required to determine how cardiovascular risk might be reduced by improving oral health.

PROJECTION FOR FUTURE STUDIES:

The saliva pH level in our group of patients with periodontal disease was lower than that reported in other studies, motivating us to further research saliva chemical and microbiological composition on a larger scale in a Romanian population to explain what could influence these values in our country.

Further studies regarding the impact of oral health in patients with chronic diseases in our country are needed, and a regular follow-up program could be developed through the close collaboration with fellow dentists.

Conclusions

A low saliva flow rate and a lower pH level are associated with severe forms of periodontal disease, with significant changes in these measures after performing dental hygiene, which makes them accessible markers in patient follow-up. Arrhythmia and myocardial infarction were common in our group of patients with a severe form of periodontal disease. By improving patients’ oral hygiene and eating habits and increasing referrals to dental healthcare professionals, we could have better results in treating periodontal disease and perhaps also preventing acute cardiovascular events. We consider it necessary to implement specific oral healthcare programs for patients with cardiovascular disease.

Figures

Figure 1. Final patient sample selection.

Figure 1. Final patient sample selection.  Figure 2. Saliva pH level evolution 3 months after dental scaling.

Figure 2. Saliva pH level evolution 3 months after dental scaling.  Figure 3. Saliva flow rate evolution 3 months after dental scaling.

Figure 3. Saliva flow rate evolution 3 months after dental scaling.  Figure 4. Relationship between cardiovascular disease and the severity of periodontal disease. CV – cardiovascular.

Figure 4. Relationship between cardiovascular disease and the severity of periodontal disease. CV – cardiovascular.  Figure 5. Distribution of cardiovascular disease in different stages of periodontal disease. MI – myocardial infarction.

Figure 5. Distribution of cardiovascular disease in different stages of periodontal disease. MI – myocardial infarction. References

1. Cekici A, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE, Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease: Periodontology, 2000; 64; 57-80

2. Gualtierotti R, Marzano AV, Spadari F, Cugno M, main oral manifestations in immune-mediated and inflammatory rheumatic diseases: J Clin Med, 2019; 8; 21

3. Kinane D, Stathopoulou P, Papapanou P, Periodontal diseases: Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2017; 3; 17038

4. Sanz M, European workshop in periodontal health and cardiovascular disease: Eur Heart J Suppl, 2010; 12(Suppl B); B2

5. López Silva MC, Diz-Iglesias P, Seoane-Romero JMUpdate in family medicine: Periodontal disease: Semergen, 2017; 43(2); 141-48 [in Spanish]

6. Gera I, Periodontal treatment needs in Central and Eastern Europe: J Int Acad Periodontol, 2000; 2(4); 120-28

7. Pantea M, Tancu AMC, Melescanu-Imre M, Ionescu E, Aspects of quality of life of elderly persons in relation with oral health: Rom J Stomatol, 2014; 60(4); 245-50

8. Hategan SI, Kamer AR, Sinescu C, Periodontal disease in a young Romanian convenience sample: Radiographic assessment: Br Med J Oral Health, 2019; 19(1); 94

9. Xu F, Lu B, Prospective association of periodontal disease with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: NHANES III follow-up study: Atherosclerosis, 2011; 218(2); 536-42

10. Bengtsson VW, Persson GR, Berglund JS, Renvert S, Periodontitis related to cardiovascular events and mortality: A long-time longitudinal study: Clin Oral Investig, 2021 [Online ahead of print]

11. Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S, Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: J Periodontol, 1996; 67(10 Suppl); 1123-37

12. Maoyang L, Songyu X, Zhao W, Oral microbiota: A new view of body health: Food Sci Hum Well, 2019; 8(1); 8-15

13. Emery DC, Cerajewska TL, Seong J, Comparison of blood bacterial communities in periodontal health and periodontal disease: Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021; 10; 799

14. Yoneda M, Hirofuji T, Anan H, Mixed infection of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Bacteroides forsythus in a murine abscess model: Involvement of gingipains in a synergistic effect: J Periodontal Res, 2001; 36(4); 237-43

15. Gomes-Filho IS, Oliveira MT, Cruz SSD, Periodontitis is a factor associated with dyslipidemia: Oral Dis, 2021 [Online ahead of print]

16. Reyes L, Getachew H, Dunn WA, Progulske-Fox A, Porphyromonas gingivalis W83 traffics via ICAM1 in microvascular endothelial cells and alters capillary organization in vivo: J Oral Microbiol, 2020; 12(1); 1742528

17. Farrugia C, Stafford GP, Potempa J, Mechanisms of vascular damage by systemic dissemination of the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis: FEBS J, 2021; 288(5); 1479-95

18. Loos BG, Van Dyke TE, The role of inflammation and genetics in periodontal disease: Periodontol 2000, 2020; 83(1); 26-39

19. Fine N, Chadwick JW, Sun C, periodontal inflammation primes the systemic innate immune response: J Dent Res, 2021; 100(3); 318-25

20. Beck JD, Moss KL, Morelli T, Offenbacher S, Periodontal profile class is associated with prevalent diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, and systemic markers of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6: J Periodontol, 2018; 89(2); 157-65

21. Aoki S, Hosomi N, Nishi H, Serum IgG titers to periodontal pathogens predict 3-month outcome in ischemic stroke patients: PLoS One, 2020; 15(8); e0237185

22. Chang Y, Woo HG, Park J, 2019 Improved oral hygiene care is associated with decreased risk of occurrence for atrial fibrillation and heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study: Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2020; 27(17); 1835-45

23. Pedersen AML, Sørensen CE, Proctor GB, Salivary secretion in health and disease: J Oral Rehabil, 2018; 45(9); 730-46

24. Hara AT, Zero DT, The potential of saliva in protecting against dental erosion: Monogr Oral Sci, 2014; 25; 197-205

25. Ormenisan A, Balmos A, Vlad M, Is there a relationship between obesity and periodontal diseases?: Rev Chim, 2018; 10(69); 969-73

26. Wolff A, Joshi RK, Ekström J, A guide to medications inducing salivary gland dysfunction, xerostomia, and subjective sialorrhea: A systematic review sponsored by the World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI: Drugs R D, 2017; 17(1); 1-28

27. Mandel ID, The functions of saliva: J Dent Res, 1987; 66(Suppl 1); 623-27

28. Kaufman E, Lamster IB, Analysis of saliva for periodontal diagnosis: A review: J Clin Periodontol, 2000; 27; 453

29. Mohamed R, Campbell JL, Cooper-White J, The impact of saliva collection and processing methods on CRP, IgE, and myoglobin immunoassays: Clin Transl Med, 2012; 1(1); 19

30. Javaid MA, Ahmed AS, Durand R, Tran SD, Saliva as a diagnostic tool for oral and systemic diseases: J Oral Biol Craniofac Res, 2016; 6; 66-75

31. BlomLöf J, Jansson L, BlomLöf L, Lindskog S, Root surface etching at neutral pH promotes periodontal healing: J Clin Periodontol, 1996; 23(1); 50-55

32. Schultze LB, Maldonado A, Lussi A, The impact of the pH value on biofilm formation: Monogr Oral Sci, 2021; 29; 19-29

33. Kabashima H, Maeda K, Iwamoto Y, Partial characterization of an interleukin-1-like factor in human gingival crevicular fluid from patients with chronic inflammatory periodontal disease: Infect Immun, 1990; 58(8); 2621-27

34. Dawes C, Pedersen AML, Villa A, The functions of human saliva: A review sponsored by the World Workshop on Oral Medicine VI: Arch Oral Biol, 2015; 60(6); 863-74

35. Kaczor-Urbanowicz KE, Martin Carreras-Presas C, Aro K, Saliva diagnostics – current views and directions: Exp Biol Med (Maywood), 2017; 242(5); 459-72

36. Caton J, Armitage G, Berglundh T, A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri implant diseases and conditions – introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification: J Periodontol, 2018; 89(Suppl 1); S1-S8

37. Greene JC, Vermillion JR, The simplified oral hygiene index: J Am Dent Assoc, 1964; 68; 25-31

38. Navazesh M, Methods for collecting saliva: Ann NY Acad Sci, 1993; 694; 72-77

39. Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale CP, European Society of Cardiology, European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2019, Eur Heart J, 2020; 41(1); 12-85

40. Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance: Sci World J, 2020; 2020; 2146160

41. Ferreira RO, Corrêa MG, Magno MB, Physical activity reduces the prevalence of periodontal disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis: Front Physiol, 2019; 10; 234

42. Sanz M, Marco Del Castillo A, Jepsen S, Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report: J Clin Periodontol, 2020; 47(3); 268-88

43. Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé EOral Health Collaborators, Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors: J Dent Res, 2017; 96(4); 380-37

44. Persson GR, Persson RE, Hollender LG, Kiyak HA, The Impact of ethnicity, gender, and marital status on periodontal and systemic health of older subjects in the Trials to Enhance Elders’ Teeth and Oral Health (TEETH): J Periodontol, 2004; 75; 817-23

45. Park SY, Kim SH, Si-Hyuck Kang SH, Improved oral hygiene care attenuates the cardiovascular risk of oral health disease: A population-based study from Korea: Eur Heart J, 2019; 40(14); 1138-45

46. Dursun E, Akalin FA, Genc T, Cinar N, Oxidative stress and periodontal disease in obesity: Medicine (Baltimore), 2016; 95(12); e3136

47. Salman LA, Shulman R, Cohen JB, Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management: Curr Cardiol Rep, 2020; 22(2); 6

48. Badran M, Laher I, Waterpipe (shisha, hookah) smoking, oxidative stress and hidden disease potential: Redox Biol, 2020; 34; 101455

49. Ye D, Gajendra S, Lawyer G, Inflammatory biomarkers and growth factors in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid of e-cigarette users, cigarette smokers, and dual smokers: A pilot study: J Periodontol, 2020; 91(10); 1274-83

50. Petersen PE, Ogawa H, The global burden of periodontal disease: Towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control: Periodontol 2000, 2012; 60(1); 15-39

51. Schwahn C, Polzer I, Haring R, Missing, unreplaced teeth and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: Int J Cardiol, 2013; 167(4); 1430-37

52. Boillot A, El Halabi B, Batty GD, Education as a predictor of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review with meta-analysis population-based studies: PLoS One, 2011; 6(7); e21508

53. Aframian DJ, Davidowitz T, Benoliel R, The distribution of oral mucosal pH values in healthy saliva secretors: Oral Dis, 2006; 12(4); 420-23

54. Baliga S, Muglikar S, Kale R, Salivary pH: A diagnostic biomarker: J Indian Soc Periodontol, 2013; 17(4); 461-65

55. Govindaraj S, Daniel M, Vasudevan S, Changes in salivary flow rate, pH, and viscosity among working men and women: Dent Med Res, 2019; 7(2); 56-59

56. Wang LH, Lin CQ, Yang L, Gender differences in the saliva of young healthy subjects before and after citric acid stimulation: Clinica Chimica Acta, 2016; 460; 142-45

57. Voelker MA, Simmer-Beck M, Cole M, Preliminary findings on the correlation of saliva pH, buffering capacity, flow, consistency and streptococcus mutans in relation to cigarette smoking: J Dent Hyg, 2013; 87(1); 30-37

58. Toida M, Nanya Y, Takeda-Kawaguchi T, Oral complaints and stimulated salivary flow rate in 1188 adults: J Oral Pathol Med, 2010; 39; 407-19

59. Koss MA, Castro CE, Salúm KM, López ME, Changes in saliva protein composition in patients with periodontal disease: Acta Odontol Latinoam, 2009; 22(2); 105-12

60. Alqefari J, Albelaihi R, Elmoazen R, Three-dimensional assessment of the oral health-related quality of life undergoing fixed orthodontic therapy: J Int Soc Prev Community Dent, 2019; 9(1); 72-76

61. Bel’skaya LV, Sarf EA, Kosenok VK, Age and gender characteristics of the biochemical composition of saliva: Correlations with the composition of blood plasma: J Oral Biol Craniofac Res, 2020; 10(2); 59-65

62. Rad M, Kakoie S, Niliye Brojeni F, Pourdamghan N, Effect of long-term smoking on whole-mouth salivary flow rate and oral health: J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects, 2010; 4(4); 110-14

63. Lobo MG, Schmidt MM, Lopes RD, Treating periodontal disease in patients with myocardial infarction: A randomized clinical trial: Eur J Intern Med, 2020; 71; 76-80

64. Araujo RPC, Souza DO, Araujo DB, Alves CAD, Salivary flow and buffering capacity in patients with cardiovascular disease: Bras Res Pediatr Dent Integr Clinic, 2013; 13(1); 229-34

65. Loesche WJ, Periodontal disease as a risk factor for heart disease: Compendium (Newtown, Pa), 1994; 15(8); 976-82 passim;quiz 992

66. Kubala E, Strzelecka P, Grzegocka M, A review of selected studies that determine the physical and chemical properties of saliva in the field of dental treatment: Biomed Res Int, 2018; 2018; 6572381

67. Kwon SC, Wyatt LC, Li S, Obesity and modifiable cardiovascular disease risk factors among Chinese Americans in New York City, 2009–2012: Prev Chronic Dis, 2017; 14; 160582

68. Yamashita JM, de Moura-Grec PG, de Freitas AR, Assessment of oral conditions and quality of life in morbid obese and normal weight individuals: A cross-sectional study: PLoS One, 2015; 10(9); e0137707

69. Tonetti MS, Van Dyke TEWorking group 1 of the joint EFP/AAP workshop, Periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases: J Periodontol, 2013; 84(Suppl 4); S24-29

70. Tonetti MS, Eickholz P, Loos BG: J Clin Periodontol, 2015; 42(Suppl 16); S5-11

71. Graça SR, Albuquerque TS, Luis HS, Oral health knowledge, perceptions, and habits of adolescents from Portugal, Romania, and Sweden: A comparative study: J Int Soc Prev Community Dent, 2019; 9(5); 470-80

72. Eaton KA, Carlile MJ, Tooth brushing behaviour in Europe: Opportunities for dental public health: Int Dent J, 2008; 58; 287-93

Figures

Figure 1. Final patient sample selection.

Figure 1. Final patient sample selection. Figure 2. Saliva pH level evolution 3 months after dental scaling.

Figure 2. Saliva pH level evolution 3 months after dental scaling. Figure 3. Saliva flow rate evolution 3 months after dental scaling.

Figure 3. Saliva flow rate evolution 3 months after dental scaling. Figure 4. Relationship between cardiovascular disease and the severity of periodontal disease. CV – cardiovascular.

Figure 4. Relationship between cardiovascular disease and the severity of periodontal disease. CV – cardiovascular. Figure 5. Distribution of cardiovascular disease in different stages of periodontal disease. MI – myocardial infarction.

Figure 5. Distribution of cardiovascular disease in different stages of periodontal disease. MI – myocardial infarction. Tables

Table 1. Periodontal status and oral healthcare habits in the study group.

Table 1. Periodontal status and oral healthcare habits in the study group. Table 2. Patient reevaluation 3 months after oral hygienization.

Table 2. Patient reevaluation 3 months after oral hygienization. Table 3. Logistic regression (using Enter method) with cardiovascular disease as a dependent variable.

Table 3. Logistic regression (using Enter method) with cardiovascular disease as a dependent variable. Table 1. Periodontal status and oral healthcare habits in the study group.

Table 1. Periodontal status and oral healthcare habits in the study group. Table 2. Patient reevaluation 3 months after oral hygienization.

Table 2. Patient reevaluation 3 months after oral hygienization. Table 3. Logistic regression (using Enter method) with cardiovascular disease as a dependent variable.

Table 3. Logistic regression (using Enter method) with cardiovascular disease as a dependent variable. In Press

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Comparison of Outcomes between Single-Level and Double-Level Corpectomy in Thoracolumbar Reconstruction: A ...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943797

21 Mar 2024 : Meta-Analysis

Economic Evaluation of COVID-19 Screening Tests and Surveillance Strategies in Low-Income, Middle-Income, a...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.943863

10 Apr 2024 : Clinical Research

Predicting Acute Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19: Insights from a Specialized Cardiac Referral Dep...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.942612

06 Mar 2024 : Clinical Research

Enhanced Surgical Outcomes of Popliteal Cyst Excision: A Retrospective Study Comparing Arthroscopic Debride...Med Sci Monit In Press; DOI: 10.12659/MSM.941102

Most Viewed Current Articles

17 Jan 2024 : Review article

Vaccination Guidelines for Pregnant Women: Addressing COVID-19 and the Omicron VariantDOI :10.12659/MSM.942799

Med Sci Monit 2024; 30:e942799

14 Dec 2022 : Clinical Research

Prevalence and Variability of Allergen-Specific Immunoglobulin E in Patients with Elevated Tryptase LevelsDOI :10.12659/MSM.937990

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e937990

16 May 2023 : Clinical Research

Electrophysiological Testing for an Auditory Processing Disorder and Reading Performance in 54 School Stude...DOI :10.12659/MSM.940387

Med Sci Monit 2023; 29:e940387

01 Jan 2022 : Editorial

Editorial: Current Status of Oral Antiviral Drug Treatments for SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Non-Hospitalized Pa...DOI :10.12659/MSM.935952

Med Sci Monit 2022; 28:e935952